Async Part 1 - Why Async

In 2012 C♯ 5 introduced the await and async keywords for expressing asynchronous

operations. Since then the model has become pervasive, spreading to languages

like JavaScript, Python, and C++. Over a series of articles I plan to explain

why async is useful and how some languages implement it.

Why care about async anyways

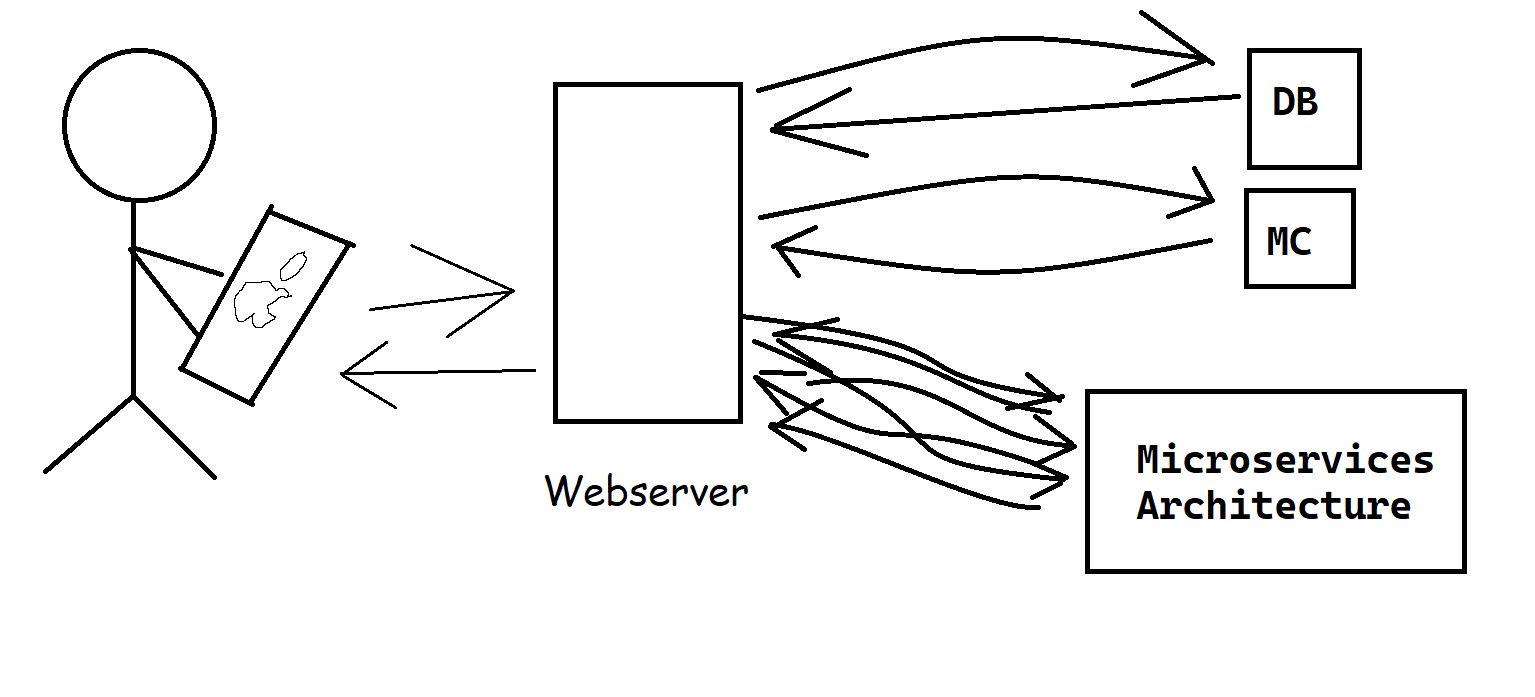

Before we get into how async works, let's take a step back and talk about why it is useful. Imagine you are building a website or a mobile application. People using your application are going to make requests to view information. Your application server probably does not have all the information needed to answer these requests. It is going to have to query databases, caches (memcache, redis, etc.), or microservices:

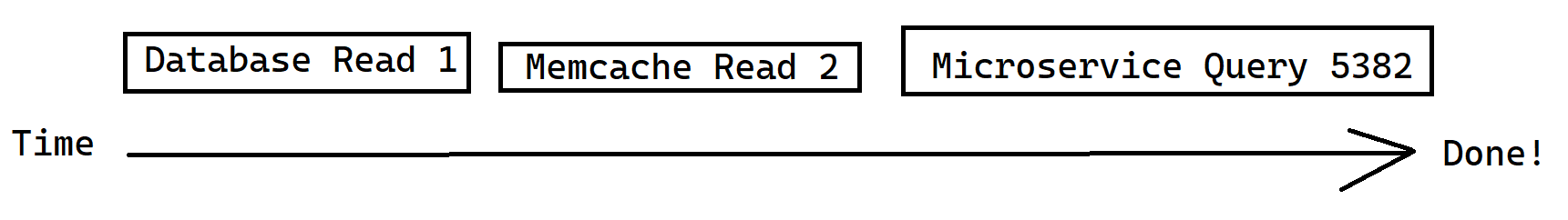

When getting all the data needed to render a webpage, the webserver will need to make a lot of queries. Each query takes some time to travel across the network and complete. If we wait for one request to complete before issuing the next, it can take a long time:

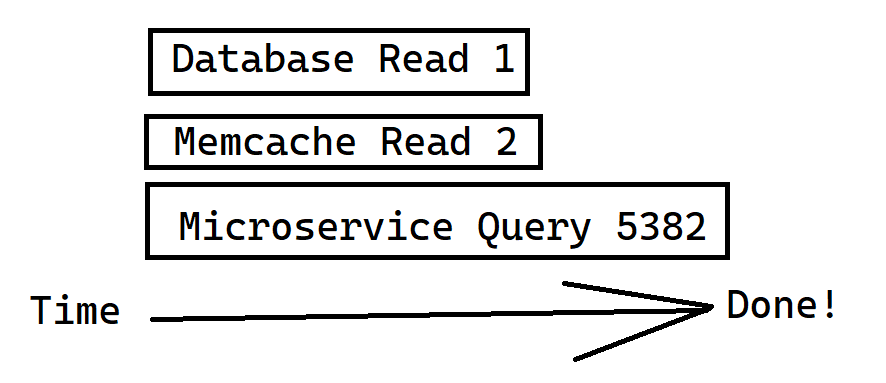

If we can issue many requests at the same time, the total amount of time to get all the data should be shorter:

The key property in an async system is "non-blocking". The thread of execution is not blocked while a task is performed asynchronously.

Systems that predate async/await

The idea of concurrently executing many different IO operations at once is pretty old. Before async/await, asynchronous programming was more cumbersome due to lack of language support. Old programming models include:

- Creating a new thread for every operation

- Green threading schedulers (libtask, Go-lang)

- Callbacks

- Promises

- Polling

- Eventloops

- Asynchronous Procedure Calls!

Each of these approaches has advantages and disadvantages. Using blocking calls on manually managed threads can be expensive, as every thread requires resources like stack virtual memory and operating system bookkeeping. I'll go into this more in my article of about schedulers.

Green thread scheduler systems improve on the resource utilization of thread threads by managing the task switching in user mode instead of the operating system. They provide APIs that look pretty similar to blocking APIs. The downside is the concurrent behavior is hidden behind these API calls and the APIs provided to manage concurrent tasks are fairly low level: things like locks and communication channels. So the programmer still has to do a lot of work when dealing with multiple concurrent tasks.

The rest of the APIs styles all require the programmer to radically re-architect

their program to fit into the system. A well known contemporary example is

callback hell in JavaScript.

Before await was added to JavaScript, asynchronous programming typically required

writing callback functions for each asynchronous operation. It is hard enough to

express and understand the control flow when everything goes right. Handling

errors is even more complicated:

function downloadContactList(onContactsDownloaded, onContactsFailure) {

serviceLocator.findServer('contacts', function (serverName, locateFailure) {

if (locateFailure) {

onContactsFailure(locateFailure);

}

else {

webClient.downloadJson(serverName, '/contacts', function (jsonPayload,

wcFailure) {

if (wcFailure) {

onContactsFailure(wcFailure);

} else {

var contacts = contactParser.parse(jsonPayload);

onContactsDownload(contacts);

}

});

}

});

}

The fundamental problem is these async systems make it difficult to compose multiple asynchronous operations with each other.

Enter async functions

With async/await, expressing an asynchronous operation looks much more like

normal code:

async function downloadContactList(onContactsDownloaded, onContactsFailure) {

try {

let serverName = await serviceLocator.findServer('contacts');

let jsonPayload = await webClient.downloadJson(serverName, '/contacts');

let contacts = contactParser.parse(jsonPayload);

onContactsDownload(contacts);

} catch (error) {

onContactsFailure(error);

}

}

Next time I will write about the properties of the async/await language

feature.